The Tutu Leadership Fellowship requires each participant to write an essay on leadership in Africa. The quality of submissions is very high as demonstrated by this challenging and thought provoking piece by 2016 Fellow Jon Kornik, where he posits that we are decades too late for leading by looking in the rear view mirror when faced with a dynamic and disrupted future. New values, new mindsets and approaches are needed in leaders for positive outcomes for the people of Africa.

It's the end of the world as we know it: Africa's leadership challenge in a disrupted future

Jon Kornik

August 2016

I am obsessed with The Future. The Future in which the current world order and dominant political systems could be completely disrupted by an evolving set of global incentives and an unyielding drive for technological progress. Technological progress which will likely lead either to the extinction or immortality of the human race within the century. I believe that my daughter will live through the most critical moments in our species’ existence that have ever been, or likely will ever be.

And yet the more I observe the actions of my leaders in Africa and the deeper I dive into literature on the topic, the more it seems that our narrative focuses largely on The Past or The Present. We correctly point out the adverse impact that colonialism has had on African social and leadership structures. We observe how Western democratic models are often at odds with traditional governance models and can lead to perverse outcomes when combined with weak institutions and corruptible leaders. We sentimentalize a few great men who have achieved incredible feats of leadership in their countries, and wish that our current leaders had the same ethical compasses. We look to success stories in the West and Asia in driving economic growth and prosperity and think that similar success awaits those who emulate those policies. We treat the issues currently facing our nations, from education to healthcare to equality, as static issues which once remedied will allow us to advance to a higher plane of development.

In this essay I posit that we are decades too late for leading by looking in the rear view mirror. I propose that there are three major forces that are going to completely alter the terrain we are trying to navigate: a fundamental shift in the world order, climate change, and advancements in machine learning and automation. I argue that if fully embraced, African values of ubuntu could position us to disproportionately benefit more from this revolution. But in order to achieve this outcome we do not just need leaders who are visionary enough to build us a bridge to The Future, but also have just the right mix of leadership qualities to mobilize and guide us over this bridge.

The Future

There are many forces at play which will direct the next steps of the human race. Given a limited wordcount in which to complete this thought experiment and a recognized ignorance on the part of the author, I have chosen to focus on the three which are of most significance in my mind.

1. A change in the world order

Our current world order was formed during the 20th century and particularly in the political aftermath of World War II. During this era, the Marshall Plan matched Europe’s need to rebuild with the US’s massive wartime industrial base and need to employ millions of returning soldiers. The US government formed an implicit deal with corporations: the government would use their postwar political position to enable access to global markets for US products and in return corporations would provide employment and basic social services (like pensions and healthcare) to their workers. As Europe rebuilt its basic infrastructure, facilitation of trade through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the OECD led to variations on a similar model. And so the US and European superpowers rose, fueled by a booming middle class who had better services and more security than ever before.

The 1960s saw a few technological advancements which enabled Asia to share in these spoils: airliners became capable of nonstop service between the US and Asia, the first transpacific telephone cable was completed, and global agreement on the standardization of shipping containers was reached. This enabled products to be designed in a company’s home market and manufactured in Asia. Those Asian nations who best positioned themselves for this opportunity benefitted immensely, particularly China.

But the benefits of this increase in globalization accrued largely with the owners of multinational corporations while workers in the US and Europe saw their livelihoods incrementally exported abroad. Over time, people in these nations have become increasingly disenfranchised and angry at the system, leading to a rise of movements on either side of the political spectrum. Brexit and Donald Trump are just two symptoms of this fallout.

Until a fundamentally new operating system is developed, the likelihood of turmoil (and particularly protectionism) will only increase. We live in a different world to the one in which the Asian Tigers were born, and new strategies for development are required.

2. Climate change

We have passed the point of no return. Countries’ collective commitments under the Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are likely insufficient to move us off a trajectory towards the catastrophic impacts of climate change. And boy, do these impacts have the potential to be catastrophic.

More than 600 million people living in low lying areas are at risk of being displaced by rising sea levels. In addition, changing agricultural and disease patterns could have significant first order impacts on employment, food security and health outcomes, and second order impacts through local and regional conflicts. If this transpires, it is possible that there could be an order of magnitude increase in the number of global refugees above 2015’s record 60 million. One has to look no further than Syria and Europe to get a taste for the human, social and political fallout that could result from such an upheaval.

3. Machine automation and intelligence

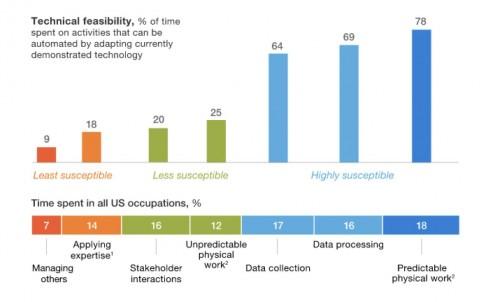

According to McKinsey & Company, advances in machine learning and robotics have led us to the point where an estimated 45% of the activities people are paid to perform can already be replaced by machines. This trend will continue as technology advances further. As this will not affect all occupations equally, policy makers should pay careful consideration to the future workplace when promoting policies aimed at skills development and employment.

These choices are made even more difficult by the unpredictable pace of technology development. One major uncertainty is driven by the feasibility and timing of the Singularity the point at which machines overtake their human counterparts in intelligence. At this point, machines could theoretically accelerate incremental gains in machine intelligence much faster than humans, radically changing civilization. Most experts predict this moment to occur sometime between 2030 and 2080.

The Promise of Ubuntu

According to Barbara Nussbaum, ubuntu can be defined as “the capacity in African culture to express compassion, reciprocity, dignity, harmony and humanity in the interests of building and maintaining community with justice and mutual caring”. In this section I argue how powerful this values system is in confronting the challenges outlined above, and the need for African leadership to adapt to reverse ubuntu’s decline in popular culture.

The three forces of The Future outlined above have the potential to be deeply destructive to personal welfare, and as a result, tear our local and global communities apart as individuals try to protect themselves and their families: incrementally declining welfare and growing discontent in yesterday’s superpowers leading to protectionism and fear of other cultures; major disruptions from climate change leading to further erosion of welfare and exacerbation of conflict; and machines which increasingly encroach upon our occupations and threaten our financial security.

Imagine how a society built on a foundation of ubuntu could deal with these challenges. Rather than focusing on a rhetoric of divisiveness in the face of discontent, people could take a step back and consider how a sweeping change in the system could be designed to benefit the collective, not just the individual. Communities, corporations and governments could step in to fill the void as individual welfares declined. Conflicts could be reduced as we proactively cared for the disenfranchised with dignity rather than desperately protecting what is ours. Machines could work for us, supplying us with a living wage and expanded free time to explore our passions.

One of the most striking illustrations of The Future with and without ubuntu is outlined in Marshall Brain’s short story, Manna. The story paints a future in which machines have significantly advanced in intelligence and capabilities, and describes how this future has played out in two different societies.

In the first, the corporations who developed and own the machines have accrued inordinate wealth at the expense of the masses who have seen their occupations destroyed. The few people who are lucky enough not to be restrained in camps on the outskirts of towns are essentially extensions of the machine blindly following menial orders issued by a central intelligence which keeps the entire organism moving in its desired direction. In the second, the wealth is essentially accrued by every individual in society: the machines mine resources, produce energy, grow produce, manufacture goods, ensure safety and provide all of these goods and services to the masses for free. People in this society spend their days pursuing their passions which leads to the further advancement of society engaging in advanced research, exploring artistic and cultural boundaries, spending time with friends and family, playing games.

So what has happened to ubuntu in Africa? Be it through convergence or divergence of economic ideology and cultural values, this has been progressively eroded by our leaders and forces like urbanization. Political leaders spew a rhetoric of divisiveness and tribalism in order to garner votes and political power. Civil society leaders often fight tirelessly for the welfare of their constituents even if this is at the expense of the advancement of society as a whole. Business leaders fight ruthlessly for greater market share and profits, prioritizing their fiduciary duties to shareholders over society.

Sitting on the cusp of this revolution, we need leaders who recognize the importance of crossvergence selecting the pieces of economic ideology and cultural values that can be melded to achieve the best societal outcome. We need leaders who live the values of ubuntu in all of their dealings and popularize its impacts on society. Leaders like Nelson Mandela who donated one third of his presidential salary towards assisting disadvantaged children, rather than pushing the boundaries of how much can be extracted from taxpayers to fund a personal residence. Leaders like Leopold Senghor who preached a gospel of inclusiveness, rather stoking the fires of tribalism and

separation. Leaders like Warren Buffett who has pledged to give all of his stock in Berkshire Hathaway and 99% of his wealth to philanthropic foundations and inspired 139 billionaires to do the same to the tune of $365B, rather than seeing how many private islands he could accumulate. It should be the norm for our leaders to pay it forward so that the rest of society can be inspired to follow.

An even greater leadership challenge

Unfortunately it is not sufficient for our leaders only to achieve the monumental task of redirecting an entire society’s cultural norms, albeit back towards its natural state. In this section I argue that we also need leaders who are charismatic enough to be given the opportunity to confront this challenge, visionary enough to develop the best strategies for positioning their nations and organizations for the The Future, and who have the capabilities to mobilize their followers in this new direction.

The only thing that is certain about The Future is that it is uncertain. While I have posited some potential outcomes of the three global forces above, it is impossible to know for sure how these will transpire in the face of numerous additional global trends and complex and interrelated geopolitical considerations. Additionally, given different starting points and capabilities, the optimal strategies will likely differ substantially across countries and organizations. We need visionary leaders whose gaze can pierce through this sea of ambiguity to define the best paths for their followers. But in order for followers and incumbents to heed these words, leaders will need to be charismatic enough to paint a compelling enough picture of the future.

But defining the best path and getting people to listen is also not enough. We need mobilization leaders who are able to lead us along this path into The Future. The traits required in these mobilization leaders will differ by country depending on the unique challenges for overcoming inertia. Depending on the national culture, charismatic or patriarchal leadership may be required to build a strong following. Or failing that, disciplinarian leadership could be needed to force society in the required direction. Reconciliatory leadership may be necessary to mend fissures between tribes, races and religions and enable followers to work together. Technocratic leadership may be necessary to determine how institutions should adapt to enable the achievement of the set strategy.

With such a major global disruption and change in the status quo, there will almost certainly be opportunity for well positioned individuals to accumulate significant power and wealth. We somehow also need deeply ethical, principled and incorruptible leaders who we can trust to continue to live the values of ubuntu.

So what can we do?

In outlining the types of leaders we need, I realize that I have listed six of Mazrui’s eight typologies of leadership, in addition to rare personal traits like the personification of ubuntu, unwavering ethics and incorruptibility. From a South African perspective, I do not believe that our current leaders display all of these characteristics nor have their actions indicated that they are willing or capable of developing into the type of leaders we need. Rather, a fresh set of leaders will be required to ascend to power. In this conclusion I question whether this is even possible, and hypothesize about how this leadership change can be brought about or accelerated.

I imagine a world where three types of societies exist: dystopian states where humans are enslaved to corporations and machines (the first society from Manna), utopian states where machines serve all humans equally for the benefit of individuals and society (the second society from Manna), and volatile states where despotic leaders use machines to control their populations and seek power beyond their borders by any means.

I believe that all three of these societies could exist, and that African countries have a better chance than most of achieving utopia. Firstly, while the leadership challenges outlined above are significant, our younger democracies carry less political debt to prevent the required systemwide changes (compared to countries like the US where partisan politics has been shown to significantly slow progress, for example during Obama’s term). Secondly, with more than 15% of the world’s population residing in Africa, there is a reasonable probability that our continent will produce numerous leaders with the required potential. Thirdly, we already have the cultural foundations of ubuntu which I have argued could be critical in this transition.

The three major barriers I see to the right leaders ascending to power are:

- creating enough of these leaders so that a few can emerge through the noise of politics,

- developing enough societal recognition of the challenges and opportunities facing us, and

- fighting the entrenched interests of corruptible incumbents.

Improved education is key to addressing the first barrier of multiplying the number of appropriate leaders. We need more world class education systems with content and instructional techniques tailored towards the challenges of The Future. Organizations like the African Leadership Academy (and hopefully the planned African Leadership Universities) with curricula founded on leadership, entrepreneurship and panAfricanism should be replicated (with a strong focus on technology to the extent to which this is not already represented).

Access to information is key to addressing to the second barrier of societal awareness. There is no better way to encourage access to information than through universal access to energy and the internet, and ensuring that internet content remains unfiltered by authorities and unprioritized through net neutrality.

And finally, in addition to access to information, the continued fight for transparency and accountability by civil society is necessary to erode the power of entrenched interests.

While this may seem like a daunting task, I heed Nelson Mandela’s words: “It always seems

impossible until it is done”.

References

- Achebe, C. “The Trouble with Nigeria revisited”. African leadership: from the top down.

- Brain, M. “Manna”.

- Buffett, W. “My philanthropic pledge”.

- Chui, Manyika and Miremadi. “Where machines could replace humans and where they can’t

(yet)”. McKinsey Quarterly. July 2016. - Mazrui, A. “Liberation, democracy, development and leadership in Africa”. African leadership:

from the top down. - McGranahan, Balk and Anderson. “The rising tide: assessing the risks of climate change and human

settlements in low lying coastal zones”. 2007. Environment and Urbanization. - Nussbaum, B. “African Culture and Ubuntu: Reflections of a South African in America”. World

Business Academy. Volume 17, Issue 1. February 12, 2003. - Theimann, April and Blass. “Context tension: Cultural influences on leadership and management

practice”. Reflections: The SoL Journal on Knowledge, Learning, and Change. Volume 7, Number4. - Thompson, B. “The Brexit Possibility”. June 28, 2016.

- UNHCR. “Global trends forced displacement 2015”. June 28, 2015.

- “Singularity timing projections”.

- “The Giving Pledge”. Wikipedia.

Report